The Library of Congress started building their own cassette machines in the late 60s. The type of machine you see showing up these days starting being built in 1976.

These are old fashioned rubber drive play only machines with 4 track heads in reverse track configuration. They have oscillator controlled vari speed via a slider on the front of the unit. There is also a spst insert for a remote switch 1/8″ or a breath switch (rare) and an 1/8″ input allowing you to use the unit as a mini amplifier. They are manufactured by Telex in the US and made to be rebuilt. Repair centers keep 20,000 of these things on the street via a vast network of workshops. There are approximately 600,000 of them nationwide.

In the right (wrong?) hands these things can have 101 uses:

– You can use them as grungy lofi amplifiers.

– You can use them to play regular two track stereo or mono cassettes backwards

– They can play at two different base speeds (15/16 or 1 7/8)

– You can manually adjust and pitch shift from the base speed to make a tape sound like Munchkins or Satan (or both on a good day…)

– etc. etc.

PLUS they run on bizarre nicad battery packs. Once charged you are completely mobile and can do all these horrible things and more in public, on stage, or anywhere you feel compelled to carry the thing.

NLS: That All May Read

Operating Our Cassette Player

Background

Our cassette player, known as a C-1, plays recordings at commercial speed and half commercial speed. NLS/BPH distributes its talking books on standard audio cassettes designed to play at half commercial speed and using four tracks. The NLS configuration can pack up to six hours of reading time onto one cassette. The C-1 side- and speed-selector switches enable readers to play cassettes created with the standard, commercial configuration as well as the NLS talking-book configuration. The C-1 player is shipped with a fully charged, rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery that will operate the player for about six hours after being fully charged. Simply plug the player into a standard household outlet to recharge it. Remember, you can always call your library about using the NLS/BPH player.

Using the Standard Cassette Player

You can operate the C-1 on its battery, or you can take the power cord from the recessed area in the back of the player and plug it into an electrical outlet. Here is a typical sequence for reading an NLS cassette talking book.

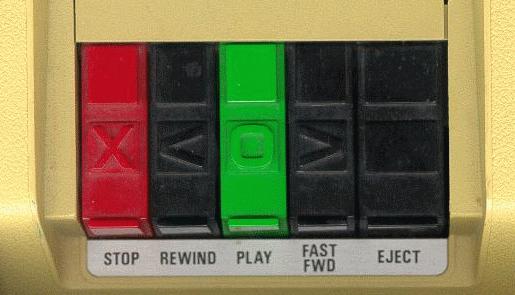

Open the tape compartment door by pressing the eject key, far right and marked with a raised square.

Insert the cassette, label side up, with the tape edge facing out. Seat the cassette by pushing it back until it clicks. Press the compartment door down until it clicks.

Press and lock down the play key (green with a raised circle) to start the player. Adjust the volume slide switch (nearest the front edge of the player).

Stop the player at any point by pressing the red key with a raised “x”, first on the left.

To review the cassette soundtrack, press rewind, the key between play and stop with the raised less-than sign, or arrow head pointing left.

To advance the cassette soundtrack, press fast forward, the key between play and eject with the raised greater-than sign, or arrow head pointing right.

To remove a cassette from the player, make sure it is stopped. Press the eject key, far right with a raised square. The tape compartment door will snap up, and the tape will pop free of its seated position. To play the next side, turn the tape over (print/braille label down), reinsert, seat in the door, and press the door shut. Then press the start key. After reading sides 1 and 2, rock the side selector switch to the right to listen to sides 3 and 4.

Tips

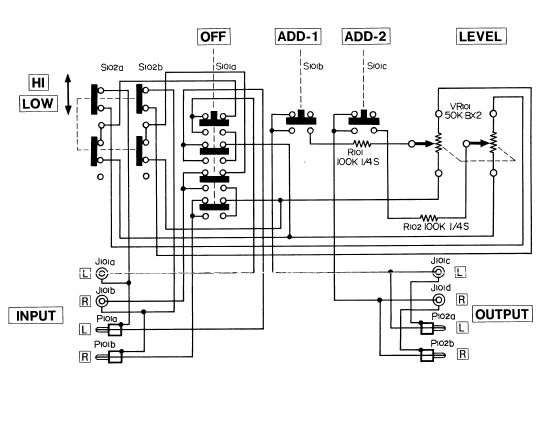

Switches and Buttons

Speed, volume, tone and side-selector switches are on the right of the player. Begin at the top of these controls, in the middle of the player as you face it, and you will find the following:

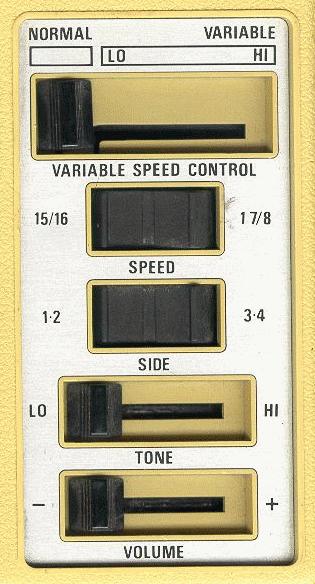

Variable Speed Control

Used to slow down or speed up the reading of the book. The voice of the narrator becomes distorted as the playback speed is changed.

Speed

A different sort of speed switch is just under the variable speed control. This is the speed switch that is used to match the speed of the player with the recording speed on the cassette. It is a rocker switch. Press, or rock it down, to the left (15/16) for our talking books. Press, or rock it down, to the right for commercial cassettes.

Side-Selector Switch

Another rocker switch, the side-selector switch enables readers to listen to both commercial and talking-book cassettes. Here are the things you should know about talking-book cassettes before you use the side-selector switch:

Talking-book cassettes will appear to be oddly numbered because of the four-side (or, four-track) system. The first side of the first cassette will be 1. The first side of the next cassette will be 5. Then, 9 and so on.

Turn the cassette over after each side.

When starting with side 1, push the side selector switch down to the left, marked 1-2. Do not change the switch to listen to side 2. Push the side-selector switch down to the right for sides 3 and 4. It is important to be methodical about the use of the side switch, or you may find yourself skipping whole segments of the book.

As guidance, the narrator will provide instructions at the end of each side.

Tone Control

This slider switch raises (to the right) or lowers (to the left) the pitch of the narrator’s voice.

Volume control

The volume control is also a slider. Louder to the right, softer to the left.

Battery Maintenance

To maintain battery life, the player should be played frequently unplugged, on battery. After several hours, up to six or until the battery fails, plug the player back into an electrical outlet to charge the battery. The player will operate, plugged in, while the battery recharges.

Do not remove the battery. As a nickel-cadmium product, it is toxic if not disposed of properly. If you suspect the player will not work because of battery problems, call the library serving you. They will arrange for a replacement player.

Obselete machines:

C 76 is Orange

C77 is White

C78 is Red

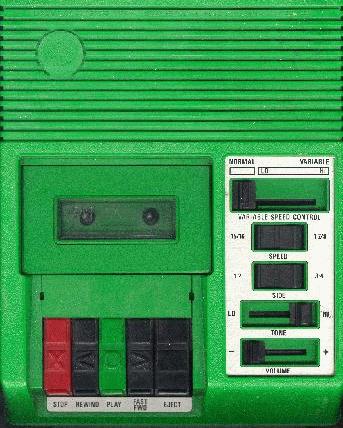

C79 is Green

C 80 is brown (they have a compression circuit but the unit sucks big time)

The 78 & 79 are by far the best units out there.

In addition there are similar plastic cased Record players:

A78 Red

A79 Green

Current machines require an appropriate license. If you find one of these you can exchange it at a local Library of Congress location for a discontinued (but equally good) model. Please do so.

C1 is Yellow

C 2 is Gray Direct drive transport

C 0 is Black ( for international users

E 1 (automated 1 control)

Record Players

A 80 Brown

A 1 Yellow

Combination machines:

CT 1 Yellow

In ’69, the first cassette machines were introduced and these played standard 2-track, 1 7/8 ips tapes. In ’73, the first 4-track machines were issued that would play at either 1 7/8 ips or 15/16 ips. Starting in the late ’70’s, most Library of Congress talking book tapes were recorded at 15/16 ips on four tracks. This enabled a standard C90 cassette to hold up to 6 hours of reading material. Tapes eventually phased out records, with the last magazines being recorded on 9″ flexible disc at 8 rpm in December, 2000. Now, digital cartridges and digital talking book players have phased out cassette tapes. Books were phased out first, followed by magazines. Somewhere, I have the last talking book magazine that I received on cassette and it’s from sometime in 2013. The library recently printed a note in it’s newsletter, telling us that they still had a small cassette book collection available to patrons who still had a cassette player in working order; however, cassette service will end when the machine fails to work because they are no longer being repaired or replaced.

It’s strange that on ebay, I’m all the time seeing talking book record players from the ’60’s until the ’90’s; but, as far as cassette players, about the only one I see is the C1 machine that was first introduced in 1981 and continued to be issued until cassette tapes were phased out. I rarely ever see any of the older tape players on ebay. I figure that part of the reason for that is because the tape players didn’t last as long as the record players and most of the older ones have probably already been turned in and replaced with newer machines. Personally, I’m on my 3rd C1 cassette player in a 14 year time period; however, many of the record players would last 20-30 years, if they were taken care of.

Eye grabbed mine off the shelf today for some tape experiments…

and was hit with total dread upon pushing transport buttons

nothing except a loud hum emitting from machine

these things are a sadistic joke on blind people trying to repair them

hidden 1/4″ hex head deep well screws hidden beneath the feet pads

was imagining some fucker laughing design this tape machine for the blind

luckily eye had my nut drivers handy

got back cover off and inside

revealing worn out stretched belt caught in main drive wheel

so……………………………………………………………………….

found the big bag o rubber bands for such occasions

took a couple attempts figuring out the belt path

first attempt did RW/FF yet was fuct on PLAY

on some further inspection the next attempt proved correct

abrahadabra!

playing better than ever

time for selecting some tapes

how about “Telepathic Communication With Animals”

or the demonstration tape for Portable Electro Shock Unit

and some tape recordings of Modular synths for further manual mutations

let’s take this baby for a spin through the Mixer with some FX!

Eye of course expect the value of mine instantly increasing by at least $100 upon completion of this post